News from a Changing Planet -- #26 -- Art in the Age of Air Pollution

What if Impressionism wasn’t a revolution in artistic style so much as an accurate representation of light in the sulfur-filled skies of the Industrial Revolution?

That is, more or less, the argument of a new paper about the effects of aerosol pollution on the painting styles of J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) and Claude Monet (1840-1926) during the first several decades of the Industrial Revolution.

Joseph Mallord William Turner, Rain, Steam, and Speed - The Great Western Railway (1844). Credit: The National Gallery.

The authors of the paper argue that all of the particulate pollutants (which came from all the coal everyone was burning all the time) scattered and absorbed sunlight in such a way that they made edges fuzzier, dulled contrast, and whitened the color of the London sky.

These optical shifts were, in turn, rendered in paint by Turner and Monet and other artists. What art historians (and everyone else) may have interpreted as developments in artistic style – an abandonment of linear perspective in favor of capturing the transience of light – may have also been a faithful depiction of how things looked: foggy, fuzzy, pastel.

To estimate the amount of particulate pollution and its effect on how things looked at the time, the authors used historical records of sulfur dioxide emissions as a proxy for total atmospheric pollution, because burning coal releases sulfur dioxide among other pollutants.

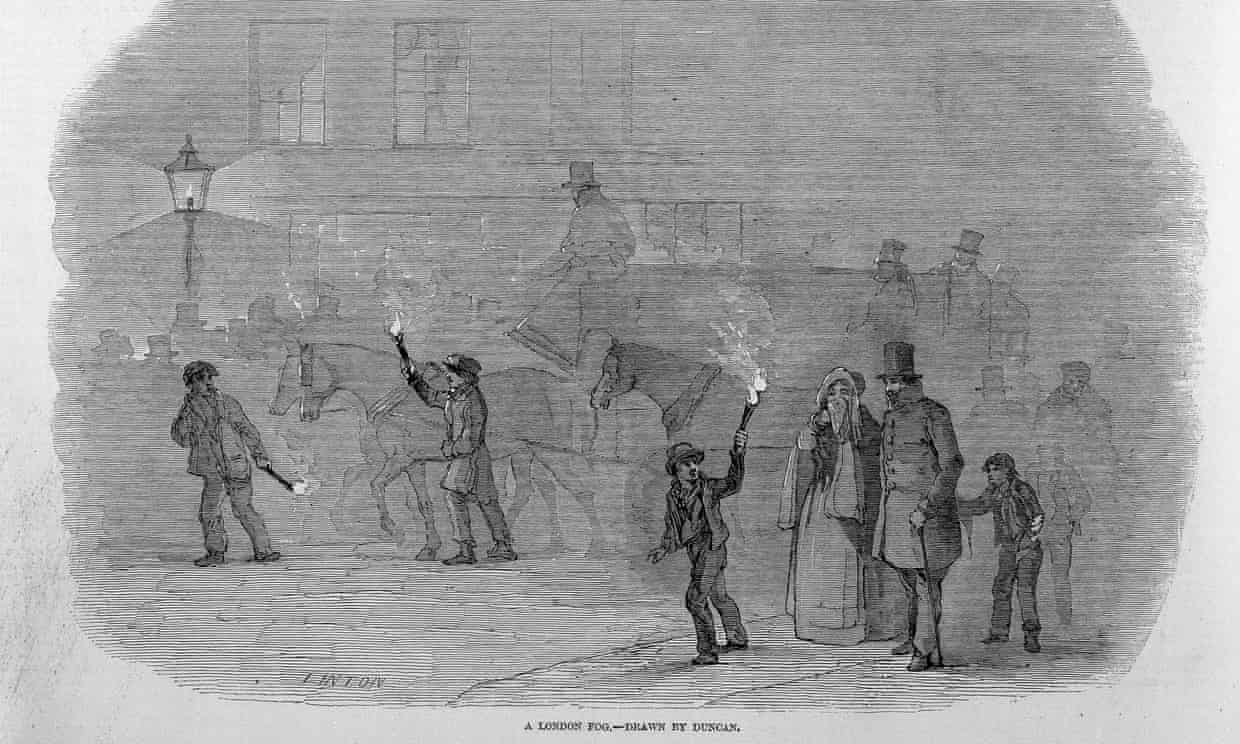

London, at the time, was known as The Big Smoke; 10 percent of all sulfur dioxide emissions in the United Kingdom puffed out of factory chimneys and trains and stoves and furnaces there despite it only accounting for about 1 percent of the U.K. by area.

An illustration of men and a boy with torches guiding people through the thick London fog. Credit: The Illustrated London News, Volume 10, 1847.

(And soot wasn’t the only environmental problem. The combination of population growth in London, hot weather, and the practice of dumping raw sewage into the Thames lead to “The Great Stink” in the summer of 1858, and the construction of the sewer system. This recent episode of the world’s best podcast, In Our Time from the BBC, on The Great Stink is especially good!)

Before 1830, the early stage of Turner’s career, visibility in clear and cloudy skies was around 15.5 miles on average. After 1830, it dropped down to 6 miles. By the time Monet got to London in the 1860s, it was rarely more than 3 miles, and the London Fog Inquiry noted that in the winter of 1901-1902 (though air quality is worse in the winter), 1 mile into the distance was about as far as anyone could see.

Claude Monet, Quai du Louvre, 1867. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Claude Monet, Waterloo Bridge, London, at Dusk (1904). Credit: National Gallery of Art

Monet and Turner weren’t the only artists for whom the study’s model held. Their model also predicted the contrast found in the works of other artists from the same era, based on the year, local SO2 emissions, and subject matter: Gustave Caillebotte, Camille Pissarro, Berthe Morisot, and James Abbott McNeil Whistler.

I love this study for lots of reasons, but mainly because it is making me think about Some Big Questions™: How do we know what we know? Can we trust what we see? Why do we construct narratives about history, politics, culture and art outside of their specific environmental and atmospheric contexts, as if we aren’t shaped by the particular version of the physical world in which we live at the time in which we live there? What does it all mean, Basil?

Typically, when I think about art, I assume that developments in artistic expression are the product of individual genius, of certain ideas, and of cultural transmission, which is, of course, true. It’s easier, maybe, to appreciate how scientific discoveries and technological advancement influence art, because they might change the way we see what we see or give us a new way of seeing it. Cameras and the mechanical way they crop reality changed how painters composed paintings – moments could be captured, and painters could now respond. The examples I always think of are Edgar Degas’s paintings of horse races, like this one.

Edgar Degas, The Jockeys (1881). Credit: Yale University Art Gallery

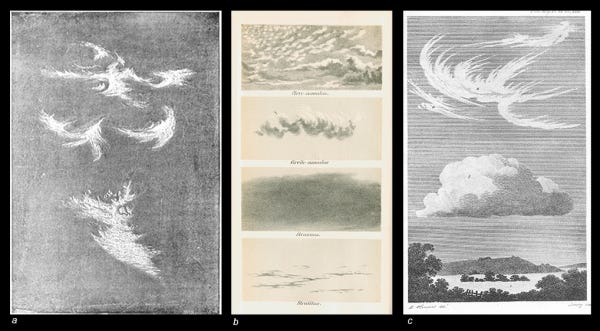

Developments in the scientific understanding of clouds and the atmosphere also changed artistic ambitions and methods of depicting them realistically. Just ask John Ruskin!

Cloud formations by (L-R) John Ruskin (Works Vol. VII, 1905); Robert FitzRoy (The Weather Book, 1863); Luke Howard (Philosophical Magazine, 1803; source: gregoniemeyer via flickr)

But it makes sense, intuitively, that what we see -- and what we know about what we see -- changes what art is made. Painters, like Turner and Monet painted the transformations of the Industrial Age, but it hadn’t occurred to me that the symptoms and not just the symbols of industrialization would also have infiltrated light itself. The haziness of the skies, the smudges of sunsets or the fuzziness of edges in paintings from this era, I assumed, were merely evolutions in style.

It’s sort of consciousness-altering to think that Impressionism, to some degree, might be a product of the light-scattering effects of air pollution, but only if we suppose that culture isn’t always created in response to the conditions in which people live. We take for granted that a landscape painting in some way or another reflects the landscape as it appeared to the painter. Why would the content stand apart from the conditions within which it was made?

This particular study has me reconsidering how we know what we see: a short of shifting baseline for a clear blue sky. When I see video footage from American cities before the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970 or the expansion of the Clean Air Act in 1972, I have largely assumed that, apart from the obvious air pollution (the gray, smoggy skies), the haziness and fuzziness and the white skies were a product of the technology. Now, our images have such high resolution, so these ones just look grainy to us.

A view of Lower Manhattan taken by a Dutch tourist to New York in 1970. Credit: Jaap Breedveld, courtesy of Ephemeral New York.

Maybe, but maybe it’s also what people saw: cities were hazier, edges were fuzzier, because light was scattered by aerosol pollution; contrast was diminished and the intensity of light was stronger. Reintroducing pollution into our understanding of images of the past can help us understand why environmental regulation is so important – it cleans up the air we breathe; it changes the physical world we live in and the way we see it, too, and therefore, how we act. Our surroundings become static, unchanging, and therefore our actions don’t seem to matter. Of course they do. The air pollution in the Industrial Revolution, and the clearing of our skies in the decades since the Environmental Movement were the result of human decisions and activities. History is contingent; time moves forward.

It also reminds me of the trickiness of particulate pollution: what air pollution does to light – scatter, reflect – also affects warming (to say nothing of the health impacts). According to a 2018 study, if all of the particulate pollution currently in the atmosphere were to disappear, the average surface temperature of the earth would warm by an additional 0.5ºC to 1.1ºC (0.9ºF-2.2ºF) because all of those particles are reflecting a lot of light (and heat) back to space. (This is known as the albedo effect.)

The Monet/Turner study ends with a brief mention of solar geoengineering, the idea of spraying lots of sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere to reflect even more light and heat back into space, and prevent further warming while we figure out how to reduce emissions and suck up lots of carbon dioxide. There are lots of things to consider about such proposals – the effects on water, crops, people, to name a few – but the authors of the study mention one I hadn’t much thought of: by increasing the whiteness of the sky, it would diminish the contrast of objects against the background of the sky around the world.

What would we see then, and how would we see it, under a white sky?